The killing of Russia’s ambassador

to Turkey on Monday evening might have prompted knee-jerk comparisons

to the 1914 assassination of Archduke Francis Ferdinand, but it almost

certainly won’t spark a World War One-type conflict. The lethal truck attack that killed 12 in Berlin a few hours later, however, could ratchet up the prospect of yet another political shock in Europe.

2016

looks set to keep throwing out unexpected, often brutal surprises right

to its end. If 1989 – the year the Berlin wall fell – was the point at

which globalization, liberal democracy and the Western view of modernity

was seen to triumph, the year now concluding might yet be seen as when

the wheels came off.

That

may be a dramatic overstatement. However, the electoral surprises of the

Brexit vote and the election of Donald Trump – as well as dozens of

other examples across the globe – are stark reminders of just how much

consensus has unraveled. The next year could see a step back towards

moderation. But it could equally see things spiral further out of

control.

The

assault on a Christmas market in the German capital has made the return

of the far right to power in Germany more plausible – even if it still

looks unlikely to happen in next year’s national vote. The Berlin deaths

could also

boost the chances of far-right National Front leader Marine LePen in France’s 2017 presidential election.

It is possible, of course, that the forces of moderation might stage something of a recovery next year – as we saw in

Austria’s presidential election, even this year extremists have not always won.

What

2016 has demonstrated most, however, is that nothing is truly

unthinkable anymore – or at least, that a host of options previously

judged unthinkable are much more likely than anyone previously thought.

What

is also clear is that we have yet to see the true implications of much

that happened in 2016. President-elect Trump is not yet in the White

House, but he – and particularly his Twitter feed – is already having a

dramatic effect.

It’s

hard to predict exactly what that might mean, but the indication so far

is that this will be a very different presidency. It may well, of

course, mean temporarily better relations with Russia – Trump’s comments

in the aftermath of Monday’s attacks explicitly tied the Ankara attack

to that in Berlin and suggested he intends to follow through on talk of

much closer collaboration with Russia, particularly on fighting Islamist

militancy. That may also imply some kind of grand bargain on Syria,

particularly with the fall of Aleppo making any opposition victory even

more implausible.

A Trump

administration, however, may well swiftly find itself much more greatly

at odds with China. Last week’s spat over the Chinese seizure of a U.S. underwater drone in the South China Sea may be a sign of things to come on that front.

The

one thing that has cemented Beijing into the international system over

the last 25 years, after all, has been that it has benefited greatly

from being part of an increasingly free international trading system –

something Trump clearly intends to push back against, if not dismantle entirely.

If British Prime Minister Theresa May is to be taken at her word, then in 2017 Brexit will really

begin to mean Brexit insofar as the UK will move to trigger Article 50 to quit the European Union. No one really knows what that will mean.

In

part, that is because no one has any concept of what the European

continent will look like politically by the end of next year. The Berlin

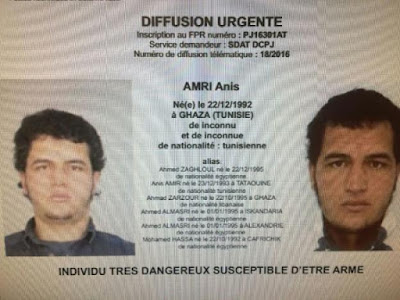

attack, whether the perpetrator is eventually found or not,

will almost certainly ramp up political pressure on Chancellor Angela

Merkel for her policies on migrants, just as attacks in France have

boosted LePen's National Front.

It seems less likely for now, that

Alternative for Deutschland

– the far right party that has taken up to a third of the vote in

several key German states this year – could itself topple Merkel. But

the party could perform well enough that she is replaced by another more

moderate figure, either from her own party or elsewhere in the

political mainstream.

A

European move to the far right is not inevitable – the failure of the

Austrian far right to gain the presidency demonstrates that. Still, even

the prospect that France, Germany and potentially other states might

see the far right take a dominant if not controlling role makes the

continent a very different place.

If nothing else, 2017 looks set to

see a major push back against the European – and to an extent much

broader – liberal ideal of open borders and trade. The EU itself may not

survive that.

Nor, for that matter, can the ongoing endurance of the always troubled single currency. The

Italian referendum earlier this month has left its government in a state of crisis, with the real prospect that the anti-euro

“Five Star”

movement might take control. An Italian exit might well spell the end

for the euro – at the very least, it would make Brexit seem relatively

small fry.

On Europe’s

eastern flank, meanwhile, Russia waits – sometimes interfering to try to

exacerbate political chaos and tilt things its way. Following the Trump

victory, the long-term future of NATO is also murky.

For

all the worries of inadvertent conflict after Monday’s assassination in

Ankara, it’s particularly striking that Turkey, Russia and Iran made it

clear they were making common cause and continuing with the meeting in

Moscow to discuss Syria. Turkey might still be a NATO member, but under

President Recep Tayyip Erdogan may also be moving closer to Vladimir

Putin.